Experiential learning: the silent revolution in management education

By Nisrine Hamdan

Director of Education EMIS Business School

At a time when practical skills and adaptability increasingly take precedence over pure theoretical knowledge, traditional teaching methods are revealing their limitations. Faced with this reality, a profound transformation is taking place in higher education, and particularly in the field of management: experiential learning. This innovative teaching approach, which places students at the heart of concrete, professional situations, is fundamentally redefining the training of future professionals.

Far from crowded lecture theaters and one-way lectures, experiential learning offers immersion in real-life issues, simultaneously developing know-how and interpersonal skills. Forward-thinking higher education establishments and business schools are now incorporating this philosophy at the heart of their educational projects, aware that graduates will not only need to know, but above all to be able to act in complex and unpredictable environments.

In this article, we explore the foundations of experiential learning, its various applications in higher education, and the prospects it opens up for the future of education.

What is experiential learning?

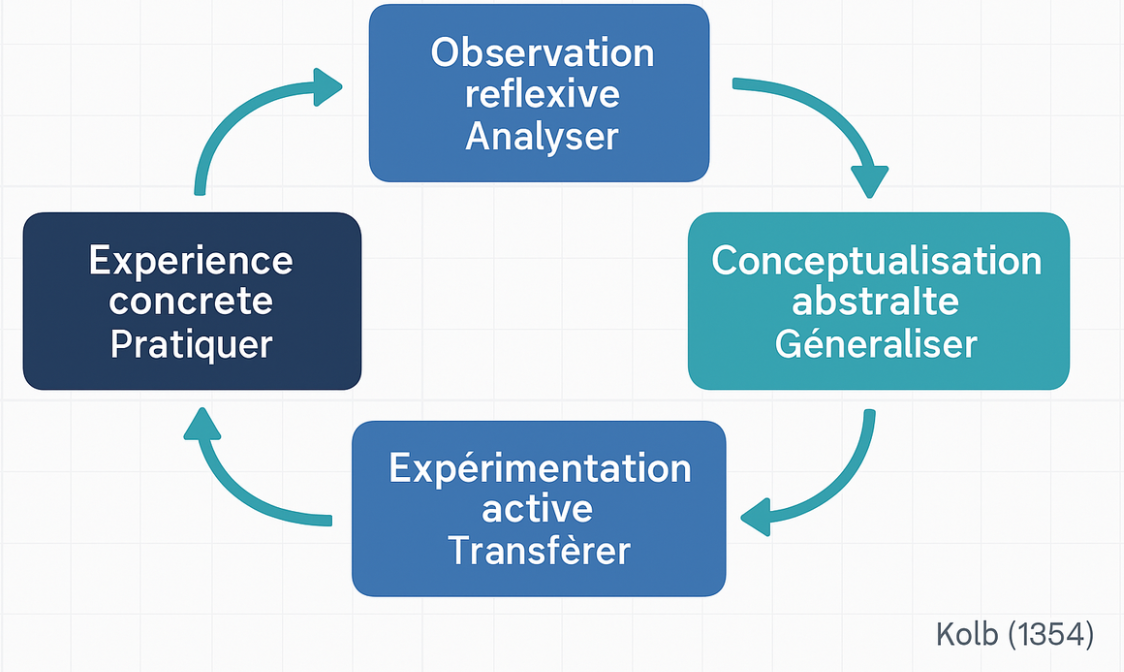

Experiential learning is based on a fundamental principle: we learn better by doing than by passively listening. Theorized by David A. Kolb in the 1980s, this pedagogical model is based on a four-phase cycle: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization and active experimentation.

Unlike traditional teaching, which favors the vertical transmission of knowledge, experiential learning places the student at the center of the educational process. They become actors in their own training, developing their skills through authentic situations that stimulate critical thinking and their ability to solve complex problems. According to Kolb (1984), for learners to be effective, they need to master four different kinds of skills: skills in concrete experience, skills in reflective observation, skills in conceptual abstraction, and skills in active experimentation. Thus, in the learning process, the learner alternates between the roles of actor and spectator, moving from active participation to a more distanced, global analytical posture.

Theoretical foundations of experiential learning

Experiential learning has a number of theoretical foundations, dating back to the early 20th century, and stemming from philosophy, psychology and the educational sciences. John Dewey (1938), an American philosopher and pedagogue, was one of the first to formalize the importance of experience in the educational process. In his book "Experience and Education", Dewey asserts that "all authentic education comes from experience", and that learning occurs when experience is transformed into knowledge through reflection.

German psychologist Kurt Lewin (1951) also made a significant contribution to this approach, developing field theory and action research. His work highlighted the importance of feedback in learning and laid the foundations for group learning, emphasizing that immediate concrete experience is the starting point for observation and reflection.

Jean Piaget (1973), with his theory of cognitive development, proposed a constructivist approach, demonstrating that learning results from the interaction between the individual and his environment. According to Piaget, intelligence develops through a process of adaptation that includes assimilation (integrating new experiences into existing patterns) and accommodation (modifying existing patterns to integrate new experiences).

However, it was David A. Kolb (1984) who synthesized these different approaches to formulate his theory of experiential learning, now widely recognized as the dominant conceptual framework in the field. His four-stage cyclical model (concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization and active experimentation) provides a structured framework for understanding how experience is transformed into learning.

Schön's (1983) work on "reflective practice" has enriched this approach by emphasizing the importance of reflection during and after action. Schön distinguishes between "reflection in action" (during the experience) and "reflection on action" (after the experience), two complementary processes that enable learners to take full advantage of their experiences.

Cognitive neuroscience also sheds valuable light on the effectiveness of experiential learning. Zull (2002) has established correspondences between Kolb's learning cycle and brain functions, demonstrating that experiential learning engages different brain regions, leading to more robust neuronal connections and longer-lasting memory.

Finally, Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences (1983) and Goleman's work on emotional intelligence (1995) also support the experiential approach, recognizing the diversity of learning styles and the importance of non-cognitive skills in professional development. Together, these approaches lay the foundations for an active pedagogy, centered on the learner and on the meaning of what he or she experiences.

The different forms of experiential learning

Experiential learning comes in a variety of formats, each offering specific benefits. In business schools, the main experiential teaching methods adopted to foster a dynamic knowledge-building process are :

Case studies : In addition to theoretical cases, students analyze existing business situations, sometimes in direct collaboration with their managers. This method, popularized by Harvard Business School since 1920, enables students to compare theories with real-life situations. According to Hammond (1980), case studies are particularly effective in developing critical analysis and decision-making skills in a context of uncertainty. Research by Bridgman et al (2016) has shown that this approach enables students to develop a more nuanced understanding of complex managerial issues, by exposing them to the multiplicity of contextual factors that influence organizational decisions.

Simulations : These immersive exercises reproduce the dynamics and challenges of the professional world in a controlled environment. Students make strategic decisions and observe the consequences, developing their ability to analyze and take a step back. According to Salas et al (2009), simulations enable the development of technical and behavioral skills in a safe environment, where error becomes a source of learning rather than failure. A meta-analysis conducted by Vlachopoulos and Makri (2017) revealed that simulations significantly improve students' engagement, intrinsic motivation and ability to transfer theoretical knowledge to practical situations.

Consulting projects : Supervised by professors and professionals, students respond to the real problems of partner organizations. This approach enables them to put their knowledge into practice while confronting the real constraints of the professional world. According to Cooke and Williams (2004), these projects constitute a "fertile learning zone" where students simultaneously develop technical, relational and methodological skills. Grossman's (2002) longitudinal study showed that students who took part in consulting projects showed a greater ability to manage ambiguity and adapt to changing professional environments.

Hackathons and innovation challenges : These intensive events, often organized over a few days, challenge students to develop creative solutions to real-life problems. They foster team spirit, time management and the ability to pitch ideas. According to Porras et al. (2019), these accelerated formats particularly stimulate collective creativity and resilience in the face of time pressure. A study by Nandi and Mandernach (2016) found that hackathon participants develop essential cross-disciplinary skills such as collaborative problem-solving and intellectual agility, while strengthening their professional network.

Bootcamps: These intensive, immersive programs, generally of short duration (a few weeks to a few months), focus on the rapid acquisition of specific skills through intensive hands-on practice. Particularly popular in the fields of IT development, design and entrepreneurship, bootcamps emphasize learning by doing and hands-on projects. According to Waguespack and Babb (2019), this accelerated pedagogical approach enables learners to acquire operational skills in record time, responding to the urgent needs of the job market.

Learning expeditions : These immersive study trips enable students to discover innovation ecosystems and different professional practices, and broaden their international vision of the world.

Learning expeditions : These immersive study trips enable students to discover innovation ecosystems, different professional practices and broaden their international worldview. According to Oddou et al (2013), these transformative experiences particularly develop cultural intelligence and the ability to adapt to unfamiliar environments. A study by Pless et al. (2011) showed that learning expeditions, when structured around precise pedagogical objectives and accompanied by time for guided reflection, enable participants to develop a global awareness and intercultural sensitivity not easily accessible in a traditional teaching setting.

Internships and work-study programs : These immersive company-based formats represent the most comprehensive form of experiential learning. Work-study programs, in particular, enable continuous cross-fertilization between theory and practice, with students able to immediately apply the concepts they have learned in the classroom in a professional situation. According to the longitudinal study by Kuh (2008), these professional experiences integrated into the curriculum are one of the most decisive factors in graduates' employability. The work of Tynjälä (2008) has shown that sandwich courses foster the development of "adaptive expertise", enabling students to navigate with ease between theoretical knowledge and its practical application in a variety of contexts.

Serious games and virtual reality: These technological tools create interactive learning environments where students can safely experiment with complex professional situations. According to Connolly et al (2012), these digital devices are particularly conducive to the cognitive and emotional engagement of learners, while enabling the personalization of the learning path. A meta-analysis by Sitzmann (2011) revealed that serious games significantly improve knowledge retention (+11%) and skills development (+20%) compared with traditional teaching methods, thanks in particular to their ability to simulate complex environments and provide immediate, personalized feedback.

Experiential learning is much more than just a pedagogical trend: it's an appropriate response to the demands of today's professional world. By placing students at the heart of real-life situations and encouraging the acquisition of practical skills, this approach is profoundly transforming higher education.

Institutions that integrate these innovative methods into their pedagogical DNA prepare their students not only to obtain a degree, but above all to become agile, operational professionals. In the specific context of MBA programs, experiential learning responds perfectly to the need to develop "soft skills" - communication, leadership, emotional intelligence and others - skills now as highly valued by recruiters as technical expertise. What's more, in an economic environment where adaptability and complex problem-solving have become essential skills, experiential learning is a real competitive advantage.

The future of higher education in general, and management education in particular, is now being written through these active pedagogies that reconcile theory and practice, reflection and action, academic knowledge and situational intelligence. For future students, choosing an education that incorporates these experiential approaches could well be decisive for their professional success.

Bibliography

- Bridgman, T., Cummings, S., & McLaughlin, C. (2016). Restating the case: How revisiting the development of the case method can help us think differently about the future of the business school. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 15(4), 724-741.

- Connolly, T. M., Boyle, E. A., MacArthur, E., Hainey, T., & Boyle, J. M. (2012). A systematic literature review of empirical evidence on computer games and serious games. Computers & Education, 59(2), 661-686.

- Cooke, L., & Williams, S. (2004). Two approaches to using client projects in the college classroom. Business Communication Quarterly, 67(2), 139-152.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. Kappa Delta Pi.

- Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Basic Books.

- GlobalEd Educators. (2013, September 10). The Harvard Business School and the case study method: Like a horse and carriage. .

- Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. Bantam Books.

- Grossman Jr, T. A. (2002). Student consulting projects benefit faculty and industry. Interfaces, 32(2), 42-48.

- Hammond, J. S. (1980). Learning by the Case Method. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School.

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Kuh, G. D. (2008). High-Impact Educational Practices. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

- Lewin, K. (1951). Field Theory in Social Science: Selected Theoretical Papers. Harper & Brothers.

- Nandi, A., & Mandernach, M. (2016, February). Hackathons as an informal learning platform. In Proceedings of the 47th ACM Technical Symposium on Computing Science Education (pp. 346-351).

- Piaget, J. (1973). Psychology and Epistemology: Towards a Theory of Knowledge. Grossman.

- Porras, J., Knutas, A., Ikonen, J., Happonen, A., Khakurel, J., & Herala, A. (2019). Code camps and hackathons in education-literature review and lessons learned.

- Raelin, J. A. (2008). Work-Based Learning: Bridging Knowledge and Action in the Workplace. John Wiley & Sons.

- Salas, E., Wildman, J. L., & Piccolo, R. F. (2009). Using simulation-based training to enhance management education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 8(4), 559-573.

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Basic Books.

- Sitzmann, T. (2011). A meta-analytic examination of the instructional effectiveness of computer-based simulation games. Personnel Psychology, 64(2), 489-528.

- Tynjälä, P. (2008). Perspectives into learning at the workplace. Educational Research Review, 3(2), 130-154.

- Vlachopoulos, D., & Makri, A. (2017). The effect of games and simulations on higher education: a systematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14, 1-33.

- Waguespack, L. J., & Babb, J. S. (2019). Toward visualizing computing curriculum: The challenge of course prerequisite dependency. Information Systems Education Journal, 17(4), 51-69.

- Wurdinger, S. D., & Carlson, J. A. (2009). Teaching for Experiential Learning: Five Approaches that Work. R&L Education.

- 24. Zull, J. E. (2002). The art of changing the brain: Enriching teaching by exploring the biology of learning. Stylus Publishing, LLC.